Keum Suk Gendry-Kim: "Titling the book 'My Friend Kim Jong-Un' led to offensive comments"

South Korean author Keum Suk Gendry-Kim explores the relationship between the two Koreas following her resounding success with the graphic novels 'Grass' and 'The Waiting'

Carlos G. Fernández

Monday, 10 November 2025, 00:30

The border between the two Koreas has been one of the hottest geopolitical zones in the world for seventy years. Both powers gesture threats, broadcast messages through huge loudspeakers, drop thousands of leaflets, and test weapons almost routinely. On Ganghwa Island, very close to this border, lives graphic novelist Keum Suk Gendry-Kim (Goheung, 1971), who refuses to accept living with daily bombings as normal.

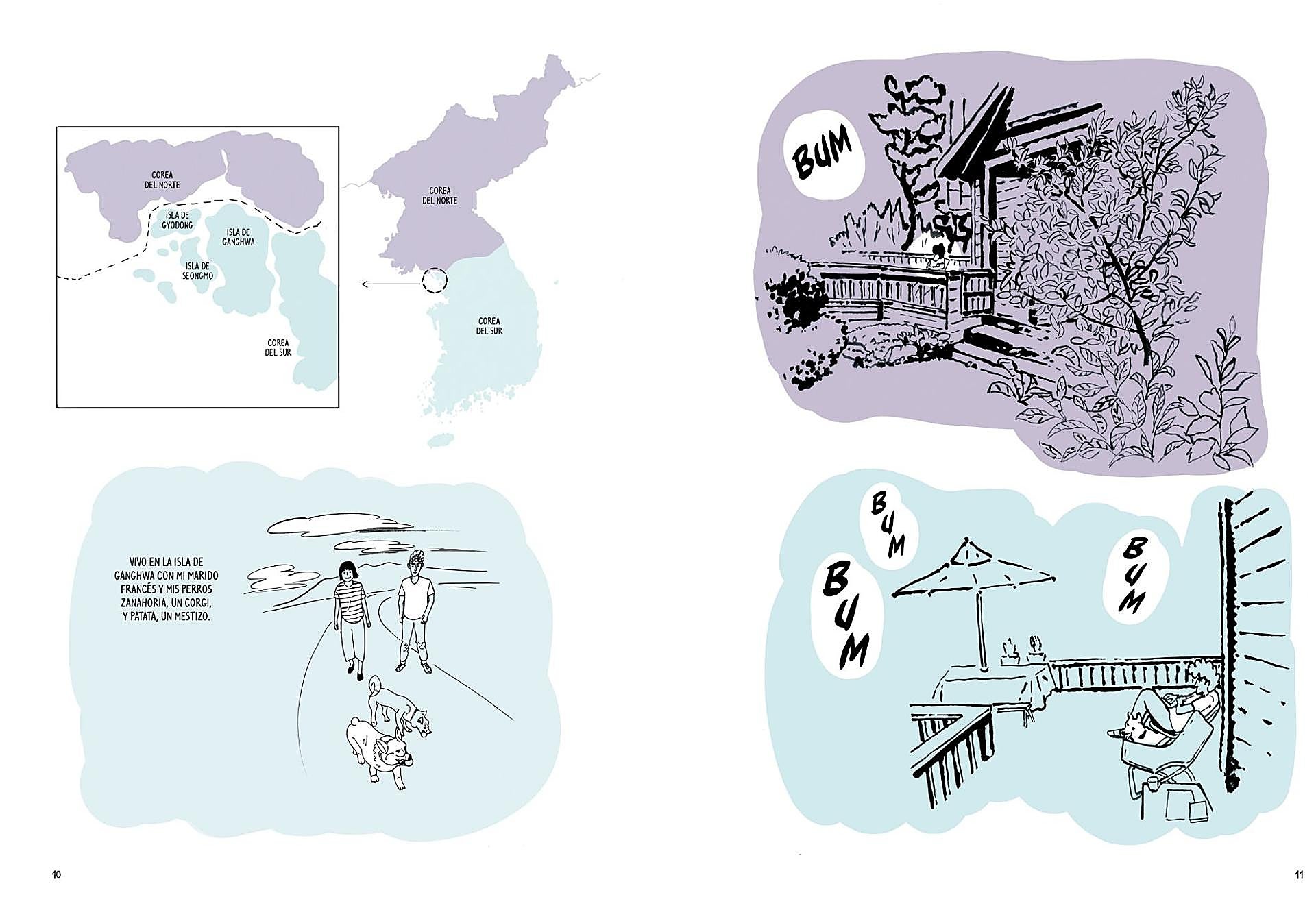

On this island begins 'My Friend Kim Jong-Un' (Reservoir Books), a comprehensive chronicle about the two souls of Korea, seeking all possible ties of union and empathy between two countries that, on paper, remain at war. "My island is very beautiful because it is not yet fully urbanised. It is close to Seoul but also to North Korea, and here people do not know me as an author. At most, they call me the dog mom because I am always walking with them," the author comments. "Perhaps I am somewhat more sensitive than other people living on the island: I am an artist, I notice things, and where I live there are many soldier drills, helicopters, and loud bomb noises. I get anxious, but the island's people are used to it."

The graphic novel persistently seeks common ground between the author's life and that of Kim Jong-Un himself. "I wanted to convey a message of peace. I thought... what is the best way to do it? And I came up with imagining what possible relationship we would have. I am from the South and he is from the North. I am an author and he is a dictator. What if we had ever crossed paths? We both lived in Europe when we were young, for example." Many facets of the North Korean leader's life, as well as the author's, are detailed.

In countries like ours, it is not very common to think that many people from both countries wish for reunification, but Gendry-Kim does not forget the humanitarian catastrophe that the division caused. "The title comes from thinking... can he really be our friend? Korea was a family that was separated. For example, my mother was separated from her older sister, who had to stay in North Korea, and they could never reunite. Now we are shooting at each other all day. That's why I decided to title it 'My Friend Kim Jong-Un', and that led to offensive comments from people who hadn't read the book. I also didn't draw him as if he were a devil; I could have played with his expression, with his eyebrows, and I didn't. I also received comments for drawing a normal, ordinary person."

Indoctrinated Children

The author returns to her childhood, to the wildest times of the propaganda war, to delve into the mentality of many of her compatriots. "We were indoctrinated, we held anti-communism competitions. I tried to be the best to earn the teachers' praise. If you collected many propaganda leaflets from the North, the police would also give you prizes." Drawing posters, anti-communist oratory contests... and one day she discovered that the South also launched propaganda, leaflets saying 'Welcome to the land of freedom and happiness' illustrated with a woman in a bikini. "In secondary school, I started reading other things, and when I went to France to study, I began to have a different perspective on what society, human beings, culture, and art are. A more open mind, also towards North Korea."

The book does not hide the tyrannies of the dynasty that rules North Korea (rival assassinations, lack of freedoms, nuclear threats...), but it promotes understanding despite everything. Gendry-Kim interviews Northern refugees living in the South, friends of Kim Jong-Un's family, and even former President Moon Jae-In, one of those who came closest to defusing the conflict. "He is a very exceptional case, a former president who loves books, has a small bookstore, and that makes him very beloved. I was lucky to be able to interview him. The people who go to his house are usually politicians, obviously. When he left office, he denied all interviews, so when I tried, he said, 'Well, you can come to my house, but I probably won't answer about North Korea.'" Gendry-Kim complied but planned to try to bring up the topic gradually. "After chatting for a while, walking, in the end, he was the one who said: 'Come on, let's get into the deep stuff.' There I saw that he was very human, a very good person."

When she was starting, it would have been difficult for her to get this interview. It is the only good thing she highlights about success because since the publication of 'Grass' in 2022 (a great success, for example, in Spain, where an estimated 70,000 copies were sold), much has changed for her. "But when I work, it has nothing to do with the success I've had. I keep talking about the topics I want to address. Before, I ran around trying to make my work known, to have many readers... now I prefer a quieter life, with more silence."

Not Everything Shines in South Korea

On the Internet, a satellite image of the Korean peninsula at night is popular: in the north, there are hardly any lights, in the south, there are millions. It is usually used as a political weapon in other parts of the world. "That image has been used in South Korea for a long time. We know that the North has suffered a lot from poverty, even now. Human rights, especially those of women, are not respected. These are very serious problems. But speaking of that image... I think that kind of propaganda doesn't make much sense. In the end, happiness is not measured by lights, that is, by money. It is not the economy that makes humans happy, nor gold or luxury brands. Happiness comes from much smaller things."

From the North come threatening news and meme caricatures, from the South other things: the unstoppable mental separation between boys and girls, isolation, aging... Keum Suk Gendry-Kim is also concerned about these. "South Korean society is full of stress. I imagine that in Spain, the mobile phone is also used a lot, but in the case of Korea, we can say that we literally live inside the mobile. It causes us a lot of fatigue, exhaustion, and stress. The baby boomers are aging, and young people have no jobs, do not want to marry, and do not want to have children. They also cannot buy houses. It is a big problem for Korean society. What happens? Young people are living off their parents' pensions. It is a serious problem."

The Graphic Novel as a Successful Format

It is undeniable that we are living in great times for the format, and Gendry Kim is today one of the most relevant names in the world. "I find it a very powerful medium. There are many books around the world about Kim Jong-Il and then about Kim Jong-Un, since he inherited power. There are biographies in English, Japanese, Korean, written by historians and specialists. What happens is that the graphic novel, this combination of image and text, is much closer to us, it generates more curiosity about a topic. And if it piques your curiosity, after reading it, you might want to read the other books written by specialists."

In this latest work, the author uses only two colours throughout the volume, a greenish-blue and a soft violet: "The most symbolic colour of South Korea was blue, a strong blue. North Korea's was red. So I thought those colours would always clash, and my message is one of conversation, of reducing the distance. So I toned down both colours, made them more diffuse, less confrontational."