Sections

Services

Highlight

Ana Vega Pérez de Arlucea

Viernes, 30 de agosto 2024, 00:05

I hope some of you work at the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (OEPM). Perhaps then this article would move from being a mere rant to a formal complaint with the potential to trigger administrative action. At worst, that hypothetical public servant could also explain why the OEPM has done something against its own rules: approving the registration of a generic sign as a trademark.

According to current regulations, signs (words, drawings, letters, numbers, etc.) that are misleading, offensive, of public interest or legally protected - such as flags, coats of arms, designations of origin or geographical indications - and generic terms cannot be registered as trademarks. In the words of the OEPM itself, generic terms are those that "in commerce or common language have come to constitute a necessary or usual designation of the product or service in question."

A chocolate bar cannot be commercially registered under the name 'chocolate,' and potato chips cannot simply be called 'potato chip,' as this would violate free competition by preventing other producers from using the same term. It should be as simple as having the officer processing a trademark application consult the RAE dictionary (or even Google!) to check if the term to be protected is a commonly used noun. As common and widespread as zurracapote, for example, which yields no less than 1,490,000 results in a quick internet search and is defined by the Spanish Language Dictionary as the word used in Álava, Albacete, Navarra, and La Rioja to refer to a refreshing drink known elsewhere as sangria, cuerva, or zurra.

Despite this, on January 26, 2020, a Guipuzcoan company was granted trademark 4025824 consisting of the name 'Zurracapote' to distinguish alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. This means that for ten years (and while it is renewed) the trademark holder has exclusive rights to use it for products based on what it was registered for. Additionally, they can prohibit others from using it for identical or similar products. In theory, neither you nor I can now use that term without the corresponding registered trademark symbol and much less offer or market zurracapote using that word. It also cannot be included in another brand or trade name, so no one else can sell zurracapote under that name but must use a convoluted formula like "flavored drink based on wine, fruit, sugar, and cinnamon."

I imagine my readers from La Rioja, Burgos, Navarra, Basque Country and Aragón are now shaking their heads in disbelief. In all these places zurracapote is popular; more than just a cousin or close relative of sangria, it is entirely and completely sangria.

We talked some time ago about the history of spiced wine and how the expensive medieval hippocras with cloves, pepper, ginger, cinnamon and nutmeg (among other exotic spices) led to more affordable and simpler versions. The most popular one made with wine, lemon, cinnamon and some honey or sugar was commonly named wine lemonade or vinous lemonade.

Sometimes diluted with water and other times fortified with liquor and pieces of dried or fresh fruit, this drink without a specific recipe received a new name from America at the beginning of the 19th century: sangria. While some places adopted that term, many Spanish regions retained other old words referring to the same concoction: lemonade (Castilla y León), cuerva (part of Castilla-La Mancha, Andalucía and Murcia), zurra (Castilla-La Mancha) and zurracapote.

In winter it was consumed hot; during Holy Week it was used to clean wounds of penitents and bearers in procession; in summer it was drunk cold—preferably iced—and made with seasonal fruits. Saying it was invented in Calahorra in the 1950s is as unfair as registering something that should belong to everyone. The oldest mention of zurracapote I have found dates back to 1860 when the Alavese town of Laguardia celebrated the capture of Tetouan with "two pitchers of wine lemonade which here is called zurracapote—a drink that greatly excites people in this country."

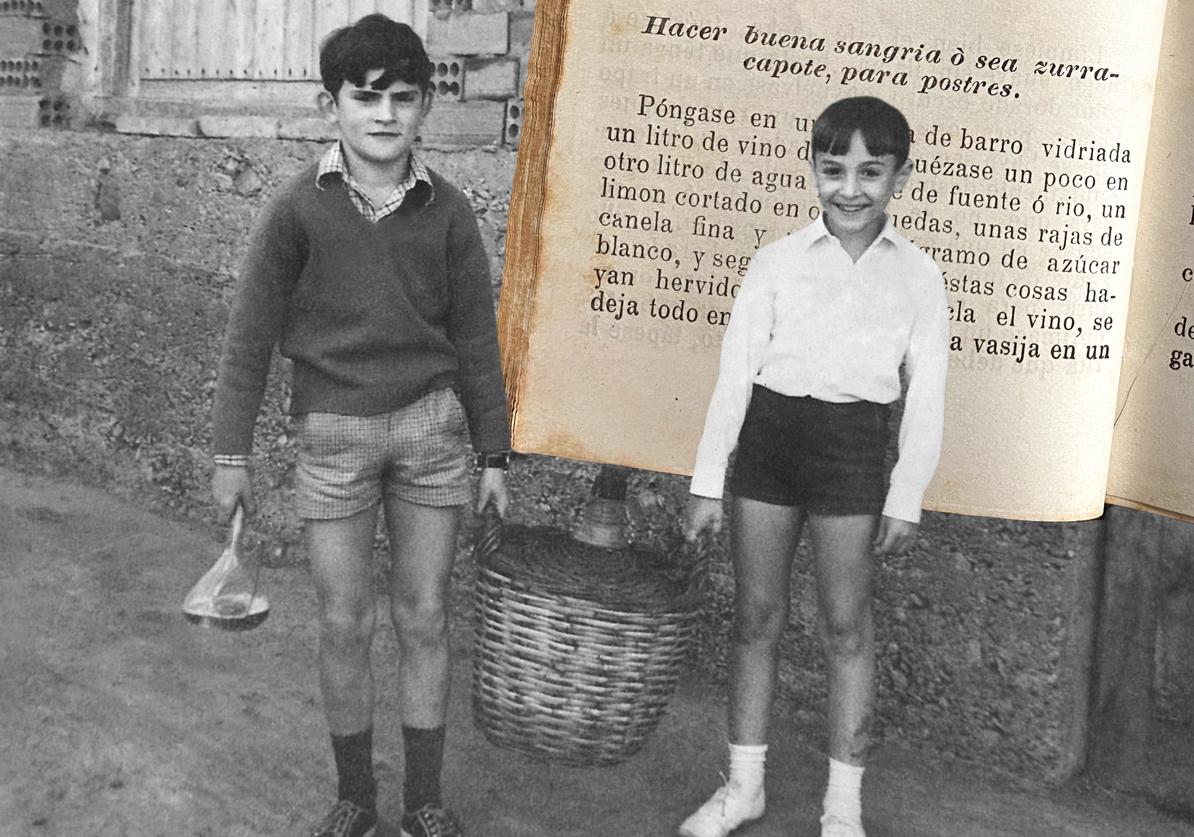

Twenty-four years later Riojan engineer Emeterio Andrés y Rodríguez published in Bilbao 'Complete Treasure of Domestic Household' (1884) including the first known recipe "to make good sangria or zurracapote." In its minimalist version it boiled in one liter of water one sliced lemon, some cinnamon and half a kilo of sugar. Then one liter of wine was added; it was left to rest; cooled down; ready "to consume before or after meals."

Not even adding peach is modern: Pastriz's (Zaragoza) zurracapote already had in 1907 "all geometric shapes that can be made with peaches." Hopefully during San Mateo festivities Logroño residents will toast by clinking their porrones for zurracapote to lose its registered trademark.

Publicidad

Publicidad

Te puede interesar

La juzgan por lucrarse de otra marca y vender cocinas de peor calidad

El Norte de Castilla

Publicidad

Publicidad

Esta funcionalidad es exclusiva para registrados.

Reporta un error en esta noticia

Debido a un error no hemos podido dar de alta tu suscripción.

Por favor, ponte en contacto con Atención al Cliente.

¡Bienvenido a TODOALICANTE!

Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente, pero ya tenías otra suscripción activa en TODOALICANTE.

Déjanos tus datos y nos pondremos en contacto contigo para analizar tu caso

¡Tu suscripción con Google se ha realizado correctamente!

La compra se ha asociado al siguiente email

Comentar es una ventaja exclusiva para registrados

¿Ya eres registrado?

Inicia sesiónNecesitas ser suscriptor para poder votar.